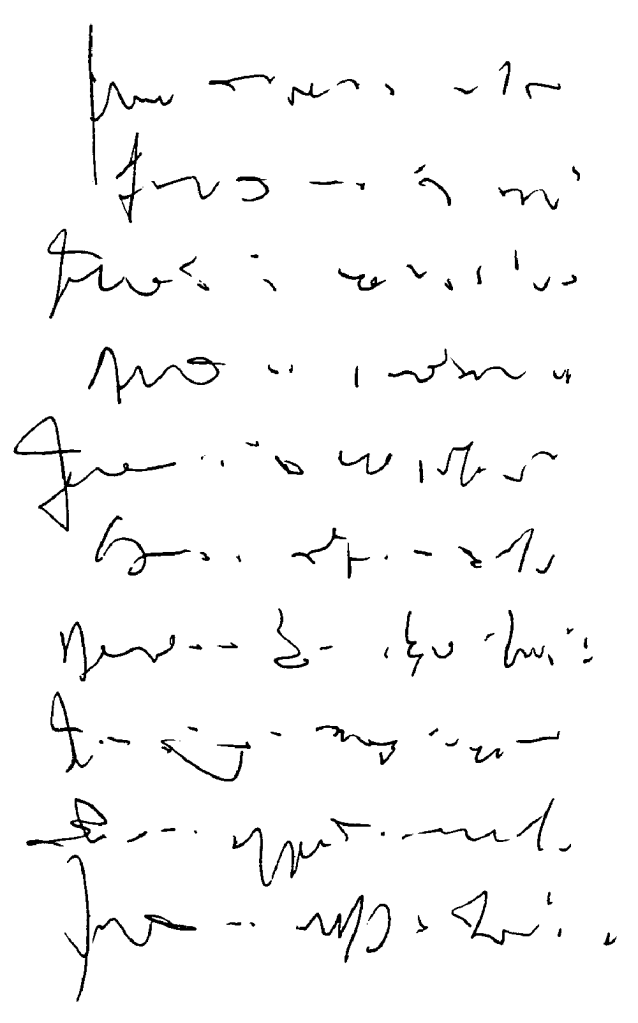

Asemic handwriting is a method of writing, perhaps close to drawing, that extends writing beyond the limits of the common established languages created by societies. It is thus much more orientated around the individual, often being more concerned with conveying thought in a more personal, emotive and spontaneous manner.

Whilst established writing languages carry semantic, emotional and aesthetic meaning, asemic handwriting bypasses the obvious semantic1 arriving at an open product without set meaning2. In summary, if asemic writing was placed on a scale, it would be this: recognisable images, abstract images, asemic writing, legible writing3.

Whilst it may sound unusual, we as people, perhaps unaware, all practise this mode of writing. For example, when we test out a pen or as children when we make mock lettering and pseudo writing when learning how to write2.

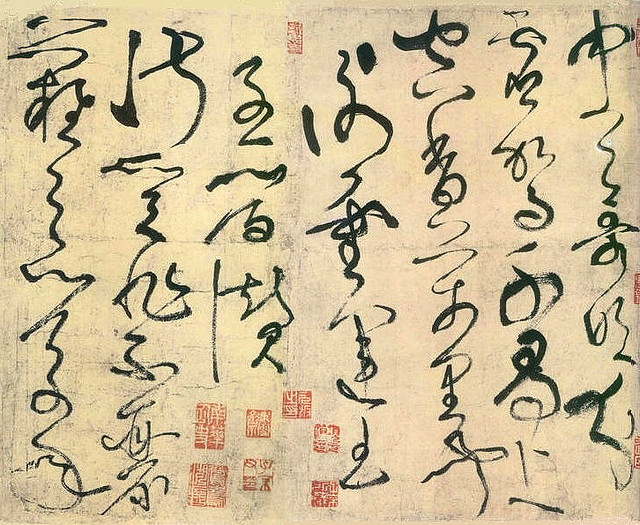

The practise of writing in this manner has been practised as far back as the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907CE), and widely across cultures. “Crazy” Zhang Xu for example was a calligrapher and poet in the Tang Dynasty who would drink in order to write in this manner (although this is optional). Further examples in more recent years include Henri Michaux, Tim Gaze and Jim Leftwich, who link this methodology of writing to poetic practise4.

The rules of this writing originate from the individual, in comparison to traditional written languages which carry a prescribed, taught format. Discussion of ‘structure vs agency’ in social theory describes the relationship between individual and society well, structure meaning the generalised, fixed features of social life and agency as the actions of the individual5. Scheper-Hughes and Lock highlight the differences between the societal body consisting of structures and relations, and the individual body which is an entity of lived experience, phenomenologically experienced6. Mauss’ Techniques of the Body describes how we learn to use our bodies in respect to societal prescriptions, and we develop cultural habitus7. Bordieu describes this as the perceptual and embodied practises that emerge in an individual over time5.

I’d argue that we see our learned societal habitus both in the way that we learn to write following existing languages, and within the characteristics of our own handwriting shapes. Our individual handwriting can be broken down to ‘style characteristics’, as learned perhaps with the handwriting guides used in school, and ‘individual characteristics’ which are personal to our body anatomy8. The asemic technique is a firm steer towards the latter ‘individual characteristics’ our bodies can produce.

Asemic writing allows us to write/record emotion as phenomenologically experienced in the body, where we might not else be able to express ourselves through the structures of language. Studies show that it can be an effective therapeutic method, such as for adults with alexithymic-schizophrenia3 as it enables a more uninhibited self-expression. There are interesting parallels occuring in anthropological discussion on embodiment and how we experience emotion and are able to describe emotion in writing. Rosaldo (1984, as cited in Lock9) believes that emotions are “culturally constructed labels to subjective feelings”(p.139), as concepts that are semantically different across cultures. Whilst unpacking the phenomenology of the body, she believes that experienced emotions are not just a cognitive judgment or visceral reaction, but both of these and more. They’re elusive and difficult to pin down9. Favret-Saada (1990, as cited in Lock9) agrees, noting that our symbolisation limits our written expression of emotion, and that sometimes emotion is ‘devoid of representation’9.

I think that asemic writing is interesting for its capabilities to express more than normative societally derived languages. It draws in more of the author, as their hand movements on the page and resultant marks are more attuned to a feeling of the individual body than prescribed shapes. Whilst it is probably not useful for the majority of communications, it can help us explore limits that prescribed languages can have on our articulations.

- Here’s a link to Tim Gaze’s website Asemic: http://www.asemic.net/

- Here’s also a pinterest board on the exploring handwriting, with many examples of asemic writing amongst examples of written languages

References

- Alsobrook, L. (2017). The Title of This Paper Is ༛༾༶༙༑༒ On Asemic Writing and the Absence of Meaning. IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities. 4 (2). pp 5-13. [Accessed 8 Mar 2020] Accessible at <https://iafor.org/journal/iafor-journal-of-arts-and-humanities/volume-4-issue-2/article-1/>

- Gaze, T, (n.d). Asemic. [Accessed 8 Mar 2020] Accessible at <http://www.asemic.net/>

- Winston, N., et al, (2016). The Therapeutic Value of Asemic Writing. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. 11 (2), pp 142-156. [Accessed 8 Mar 2020] Accessible at <https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2016.1181019>

- Gaze, T & Jacobson, M, (2013). An Anthology of Asemic Handwriting, Brooklyn, NY: punctum books.

- Kostouli, T. (2009). A sociocultural framework: writing as social practise. In: Beard et al., The SAGE Handbook of Writing Development. Sage Publications, London.

- Scheper-Hughes, N., & Lock, M., (1987). The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1(1), new series, 6-41. [Accessed 8 Mar 2020] Accessible at <www.jstor.org/stable/648769>

- Mauss, M., (1973). Techniques of the body. Economy and Society, 2(1), pp.70–88. [Accessed 8 Mar 2020] Accessible at <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03085147300000003>

- Layton, J. (2006). How Handwriting Analysis Works. HowStuffWorks. [Accessed 8 Mar 2020] Accessible at <https://science.howstuffworks.com/handwriting-analysis.htm>

- Lock, M. (1993). Cultivating the Body: Anthropology and Epistemologies of Bodily Practice and Knowledge. Annual Review of Anthropology. 22 pp.133-155 [Accessed 8 Mar 2020] Accessible at <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2155843>