“Graffiti is the visual residue of a spatialized performance that speaks to a diverse range of issues from social resistance to enacting identity.” – Tracey Bowen 1

“The possibility of a body that is written upon but also writes” – Susan Leigh Foster 2

Graffiti is a mode of writing that often carries personal style and habit. Gestures are magnified as the scale of writing is blown up and more parts of the body are engaged, which are therefore put into the work.

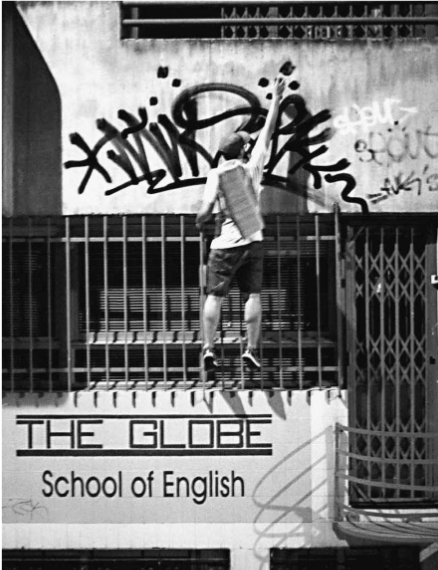

I am interested in how graffiti as a form of writing can be about performance, as a bodily act of gestures much more dynamic than perhaps on paper, and how the product of this recorded bodily movement activity shapes space.

Graffiti’s performative qualities are enacted in both the artist as they carry out the act, and as Gell notes, the viewer as they mentally rehearse the piece before them 3. This is particularly central to graffiti writing as viewer’s eyes follow the maker’s mark order as they read the words. In Bowen’s words, graffiti isn’t merely optical, but also a haptic and physical experience 1. This connection is arguably what can cause strong reactions to it 4 .

Within the performative moment of writing graffiti, it is interesting to think about the phenomenology of the body and gestures. Farnell writes about kinesthetic sense and movement as “dynamically embodied signifying acts in symbolically rich spaces”. From this, she describes the importance of bodily knowledge, the phenomenology of it as something we can mutually understand – movement which is meaningful as it is understood through our own bodily knowledge 5.

Retrieved from Schacter, R. (2014). Ornament and order : Graffiti, street art and the parergon / by Rafael Schacter. (Architecture).

Not only are gestures understood in a bodily manner, but they are understood socially as they are embodied culture 6. The idea of embodied culture is reflected by Mauss in Techniques of the body 7, and beyond this Merleau-Ponty goes as far as saying that even reflex actions are socially derived 6.

Movement and gestures are recorded in the graffiti writing, which carry semantic meaning and further emotion and intent understood socially by viewers in the body.

The individual body is connected to space through a material trace of the performance. The material deposit can become a corporeal part of its producer, an “embodiment in an object” 8. Schacter expresses this idea from his fieldwork that graffiti artists felt their work was a personification of themselves, and even a fragment of them, feeling great emotional attachments to their pieces. He even described feelings of physical injury when they were removed 4.

In thinking about space and the individual, it is interesting to think about the bodily gestures and resultant outputs as produced in space but generating space themselves, as theorised by Lefebvre 9. For example, this space generation was observed by Bowden in her observations of graffiti in Lilac Alley in the San Francisco Mission and the Queen Street Alley in Toronto1. The remains of the body in the writing seem to hold small amounts of personal or even private space within the public. This can be, not always intentionally, a territorial effect.

Graffiti-handwriting dynamically scales up the movements of the self which are put into writing. A containment of the individual and their body into a line; the body is inscribed into the work as well as the words. This I think is the most important thing in understanding the significance of handwriting.

References

- Bowen, T.(2013). Graffiti as Spatializing Practice and Performance. In: Berry E., Siegel C., 2013. Rhizomes, Issue 25. Available at <http://www.rhizomes.net/issue25/bowen/> [Accessed 2 Apr 2020]

- Foster, S. 1995. Cited in: Noland, C. (2009). Agency and Embodiment. Harvard University Press. Available at <https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0jc0.3> [Accessed 27 Mar 2020]

- Gell, A. (1998). Art and Agency. Clarendon Press.

- Schacter, R. (2008). An Ethnography of Iconoclash: An Investigation into the Production, Consumption and Destruction of Street-art in London. Journal of Material Culture, 13(1), 35–61. Available at <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1359183507086217> [Accessed 27 Mar 2020]

- Farnell, B. (2003). Kinesthetic sense and dynamically embodied action. Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement, 12(4), 132-144. <https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/59a2/ddc4d86f238c6ef509cdbd2c0efae1a76128.pdf> [Accessed 27 Mar 2020]

- Noland, C. (2009). Agency and Embodiment. Harvard University Press. Available at <https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt13x0jc0.3> [Accessed 27 Mar 2020]

- Mauss, M. (1973). Techniques of the Body. Economy and society, 2(1), 70-88.

- Dryden, 2001: 281, Cited in: Schacter, R. (2008). An Ethnography of Iconoclash: An Investigation into the Production, Consumption and Destruction of Street-art in London. Journal of Material Culture, 13(1), 35–61. Available at <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1359183507086217> [Accessed 27 Mar 2020]

- Simonsen, K. (2005). Bodies, sensations, space and time: The contribution from Henri Lefebvre. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 87(1), 1-14. Available at <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2005.00174.x> [Accessed 27 Mar 2020]

One thought on “Graffiti as a Bodily Act”