Handwriting interlinks a language with bodily movement. Whilst handwriting shows individuality among persons of a cultural group, I am interested in how we can think about the variance in taught rules between cultures such that writing displays both individual but also specific cultural identity.

Primarily, the language you write in reveals a cultural identity. But this can be broken down into ideas of prescribed movement and posture, as well as handedness. Further, some studies reveal the different biases in the movements and forms of lettering by different language-speaking groups (more later on).

Drawing back to ideas of motor habit patterns from Mauss1 and Farnell’s concept of movement as ‘dynamically embodied culture’ from my previous post, posture is certainly a component in the mechanics of handwriting that is culturally shaped2. Differences in whether we are sitting or standing to write and how we do it changes the angles, shape and contact of our hands with the writing surface.

There are both macro and micro differences in how we conduct ourselves when we write. In a more macro view, we can think about the adoption of different comfortable static positions across cultural groups in general, such as squatting, sitting cross legged, or on a chair, or standing. Postural etiquette too can drive resting posture, such as religious taboos or ideas of decorum. Certainly in english, words such as ‘slouching’, ‘lounging’ and ‘sprawling’ express a negative attitude to a non-straightened back3.

Posture is something that can be instilled from infancy3. Kipsigis, members of a farming community in western Kenya, have special words for the teaching of walking and sitting. From five months, a child is deliberately taught a sitting posture by being set in a shallow hole with blankets supporting the back. In Super’s study, they found that in comparison to these children, American infants spend 2/3rds less time sitting and when they did it was a different posture that utilised the trunk muscles less4.

Whilst I was unable to find many studies on differing modes of finger manipulation applicable to writing, handedness is another culturally entwined motor habit. Hertz discusses the beliefs towards usage of the left or right hand, and how use of the left hand is regularly suppressed amongst many cultures. For example, Maori associate the left as a side of weakness, death and misery, against the sacred right of good and creative powers5. This dualism reflected in the body is fairly common across cultures.

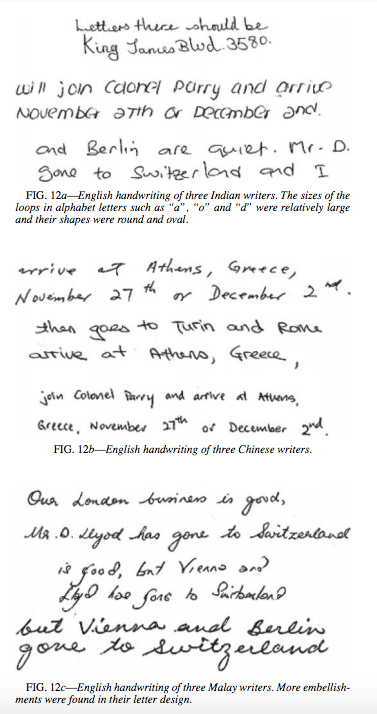

Gleaning ideas of cultural or ethnic identity from handwriting could be quite a complex task. Different cultures do however utilise different standards in the teaching of motor preliminaries for handwriting. Factors such as regularity, neatness, slant, pen lifts, clockwise or counter clockwise movements and pen grasp may be emphasised in early education to different extents6. A study by Cheng et al. examines quantitatively different qualities of Chinese, Malay and Indian natives writing in English. Using this writing system separate from their own highlighted variant writing habits and characteristics. Chinese writing consists of a variety of mark making, just as “heng” (a horizontal stroke), “shu” (a vertical stroke), “gou” (a hook), “pie” (a diagonal stroke falling from right to left) and “tiao” (a diagonal stroke rising from left to right) to name a few. In Arabic, words are written right to left and nearly every letter is joined, whereas in Tamil no letters are joined7. The study found some interesting characteristics:

- Indian (Tamil) writers frequently used more long, broad strokes with slight curvature with larger letter size

- Chinese (Mandarin) writers used more angular marks, with pen-lifts every 2-3 letters

- Malay (Arabic) writers tended to write in an anti-clockwise direction7

A further study by Saini and Kapoor looked at differences in english writing between different ethnic groups in Delhi. Some of the significant traits they observed were that the Brahmin group had a moderate right directional slant and characteristically used an inner loop formation in lower case ‘o’, whereas the Panjabi group has a vertical slant and larger line spacing. The Baniya used distinctive rounded ‘m’ humps and the Tamilian group had the smallest line spacing8. By quantitatively breaking down features of writing it is interesting to see what is prioritised collectively by members of the same cultural group.

The question as to whether you can visibly detect cultural identity in handwriting is certainly complex, and could certainly create some generalisations. However, in terms of thinking about the habitus of the body and the movements we make in tune to our cultural influences, the habit of handwriting holds space for interesting anthropological explorations.

References

- Mauss, M. (1973). Techniques of the Body. Economy and society, 2(1), 70-88.

- Farnell, B. (2003). Kinesthetic sense and dynamically embodied action. Journal for the Anthropological Study of Human Movement, 12(4), 132-144. <https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/59a2/ddc4d86f238c6ef509cdbd2c0efae1a76128.pdf> [Accessed 27 Mar 2020]

- Gordon W. Hewes. (1957). The Anthropology of Posture. Scientific American, 196(2), 122-132. Accessible at <https://www.jstor.org/stable/24941890> [Accessed 5 Apr 2020]

- Super, C.M. (1976), Environmental Effects on Motor Development: the Case of ‘African Infant Precocity’. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 18: 561-567. Accessible at <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1469-8749.1976.tb04202.x> [Accessed 5 Apr 2020]

- Hertz, Robert (1973) [1909]. The Preeminence of the Right Hand. In Right and Left: Essays on Dual Symbolic Classification. R. Needham (Ed.) Chicago: U of Chicago Press, pp. 3-31.

- Huber, R. A., & Headrick, A. M. (1999). Handwriting identification: facts and fundamentals. CRC press

- Cheng, N., Lee, G. K., Yap, B. S., Lee, L. T., Tan, S. K., & Tan, K. P. (2005). Investigation of class characteristics in English handwriting of the three main racial groups: Chinese, Malay and Indian in Singapore. Journal of Forensic Science, 50(1), JFS2004005-8. Accessible at <http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.486.7667&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 5 Apr 2020]

- Saini, M., & Kapoor, A (2014). Variability in handwriting patterns among ethnic groups of India. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. 2014b; 1 (3): 49, 60.